South Africa is being urged to accelerate its response to a looming

natural gas “supply cliff”, which could arise in the coming four to five years

unless alternative sources of supply are found to offset “tapering” imports

from southern Mozambique.

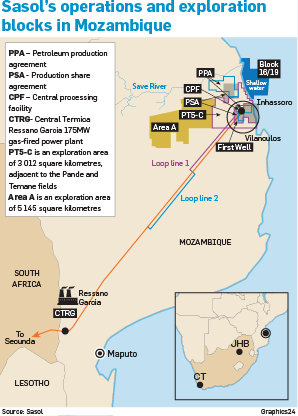

South

Africa remains highly dependent on Sasol’s Pande and Temane production areas,

with the gas used both by the JSE-listed group itself to produce fuel, power

and chemicals in Secunda and Sasolburg, as well as by various industrial

consumers in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal.Although Sasol is currently exploring

for additional gas in southern Mozambique, supply is currently scheduled to

begin falling from 2023 onwards and the Industrial Gas Users Association of

Southern Africa (IGUA-SA) is forecasting a yearly shortfall of 98-million

gigajoules from 2025 onwards.The IGUA-SA has acknowledged that the pace of the

decline may be delayed by a few years as a result of proposed investments by

Sasol in Mozambique. Nevertheless, additional sources would still be required

not only to replace dwindling Mozambican supply, but also to meet any new

industrial demand.

PwC

director capital projects and infrastructure James Mackay warns that South

Africa currently lacks both the policy and the implementation plan to avoid, or

mitigate, the potential shortfall. Speaking at the release of the latest PwC

Africa oil & gas review, Mackay said that, although significant volumes of

gas would become available in the region as the liquefied natural gas (LNG)

export projects in northern Mozambique came on line, these volumes represented

longer-term supply opportunities that would not be available in time to

alleviate South Africa’s anticipated supply constraints. The impact on the

country’s industrial economy could be significant, given that, besides Sasol,

downstream gas industries employ some 45 000 people and produce R150-billion of

economic value yearly. “Speed is more important than ever,” Mackay argued,

indicating that all the supply options available to South Africa could take up

to five years to implement, including the importation of LNG, which is viewed

by PwC as the most feasible near-term solution. Mackay believes that an LNG

import terminal at the Port of Richards Bay, in KwaZulu-Natal, represents the

“lowest-cost and least-regret” option for augmenting South Africa’s gas supply

by the mid-2020s.

He

is more sceptical, however, about the commercial viability of developing the

first LNG import terminal at the Coega Industrial Development Zone, in the

Eastern Cape, which has been held up as government’s preferred location. Unlike

Richards Bay, which has potential to immediately connect into established

pipeline infrastructure linking KwaZulu-Natal with the industrial heartland of

Gauteng, Coega is relatively isolated from areas of demand. Logistically, the

LNG would have to be transported by either road or rail inland, before being

re-gassed. This is likely to be far less cost-effective when compared with a

solution that uses an existing pipeline network and is aligned to a sizeable

market that will justify the initial terminal investment.

He

is more sceptical, however, about the commercial viability of developing the

first LNG import terminal at the Coega Industrial Development Zone, in the

Eastern Cape, which has been held up as government’s preferred location. Unlike

Richards Bay, which has potential to immediately connect into established

pipeline infrastructure linking KwaZulu-Natal with the industrial heartland of

Gauteng, Coega is relatively isolated from areas of demand. Logistically, the

LNG would have to be transported by either road or rail inland, before being

re-gassed. This is likely to be far less cost-effective when compared with a

solution that uses an existing pipeline network and is aligned to a sizeable

market that will justify the initial terminal investment.

Likewise

the IGUA-SA has argued that the Coega option “would be of no consequence to the

current user base”. In the longer-term, the development of domestic and

regional resources, including the recently discovered Brulpadda resource off

the south coast and those set to arise from northern Mozambique, could offer

supply-side relief. The massive finds in northern Mozambique, the PwC reviews

states, have already resulted in LNG project developments worth a combined

$54-billion and have the potential to turn South Africa’s impoverished

neighbour into the world’s third-largest LNG exporter. Neither of these options

would be on line in time to counteract the envisaged drop in supply from

southern Mozambique through the Rompco pipeline to South Africa. Mackay argues

that, unless a coherent solution is urgently found as to when and how the gas

shortfall will be met, and by who, there is a genuine risk that a significant

portion of South Africa’s industrial base, including companies such as Columbus

Stainless, Consol Glass, Hulamin and Nampak will be “left stranded”.

State-owned

logistics group Transnet has, together with the International Finance

Corporation, initiated a feasibility study into the development, by 2024, of an

LNG storage and regasification terminal at the Port of Richards Bay.

Nevertheless, no solution has been finalised and no procurement programme

initiated. The Cabinet-approved Integrated Resource Plan 2019 (IRP 2019) has

also not increased certainty, as it has reduced the demand for gas as a source

for electricity to 2030, making the gas-to-power programme an unlikely anchor

for the scale of gas imports required.The IRP 2019 has reduced the gas-to-power

component to 3 000 MW by 2030, from the 5 100 MW outlined in the draft IRP

2018, with the bulk of that capacity expected to arise from the conversion of

the diesel-fuelled peaking plant to gas over the coming ten years. “The gas

volumes left in the IRP are not enough to anchor the gas infrastructure

envisaged. So, we have to look more broadly than the IRP as to how to get over

this gas crunch. But at the moment, there is no policy certainty with regards

to who will do it, how it will be done and which port will be prioritised.”That

said, Mackay is heartened by recent moves by the Department of Trade, Industry

and Competition to intervene on the issue and expressed some optimism that a

national gas strategy could begin to emerge as a result of that intervention.

State-owned

logistics group Transnet has, together with the International Finance

Corporation, initiated a feasibility study into the development, by 2024, of an

LNG storage and regasification terminal at the Port of Richards Bay.

Nevertheless, no solution has been finalised and no procurement programme

initiated. The Cabinet-approved Integrated Resource Plan 2019 (IRP 2019) has

also not increased certainty, as it has reduced the demand for gas as a source

for electricity to 2030, making the gas-to-power programme an unlikely anchor

for the scale of gas imports required.The IRP 2019 has reduced the gas-to-power

component to 3 000 MW by 2030, from the 5 100 MW outlined in the draft IRP

2018, with the bulk of that capacity expected to arise from the conversion of

the diesel-fuelled peaking plant to gas over the coming ten years. “The gas

volumes left in the IRP are not enough to anchor the gas infrastructure

envisaged. So, we have to look more broadly than the IRP as to how to get over

this gas crunch. But at the moment, there is no policy certainty with regards

to who will do it, how it will be done and which port will be prioritised.”That

said, Mackay is heartened by recent moves by the Department of Trade, Industry

and Competition to intervene on the issue and expressed some optimism that a

national gas strategy could begin to emerge as a result of that intervention.

0 comentários:

Post a Comment