In

the Maninge Nice pit, the ground is literally littered with rubies. They sit in

among the dirt, throwing up glints of red and pink. We play a somewhat novel

game – who can collect the most stones in the space of a few minutes – but it’s

too easy. I get to a handful before becoming steadily distracted by the

magnitude of it all.

I

am with a group of journalists in Mozambique’s northeastern Cabo Delgado

Province, at the Montepuez Ruby Mine. Lauded as the most significant

ruby-deposit discovery of recent times, about 50 per cent of the world’s ruby

supply now comes from this mine. "Montepuez Ruby Mine covers over 33,000

hectares, making it the world’s largest ruby deposit," explains Rupak Sen,

director of marketing and sales, Asia and Middle East, for Gemfields, which

owns a 75 per cent stake in the mine. "Although the deposit was only

discovered in 2009, the rubies at the Gemfields Montepuez deposit have been

established as approximately 500 million years old."

To

boot, some of the rubies found here are of a quality previously only thought

possible in gemstones from Myanmar. "They are comparable with the

legendary ‘pigeon blood’ rubies of Myanmar, which frequently command the

highest price per carat of any coloured gemstone," says Sen.

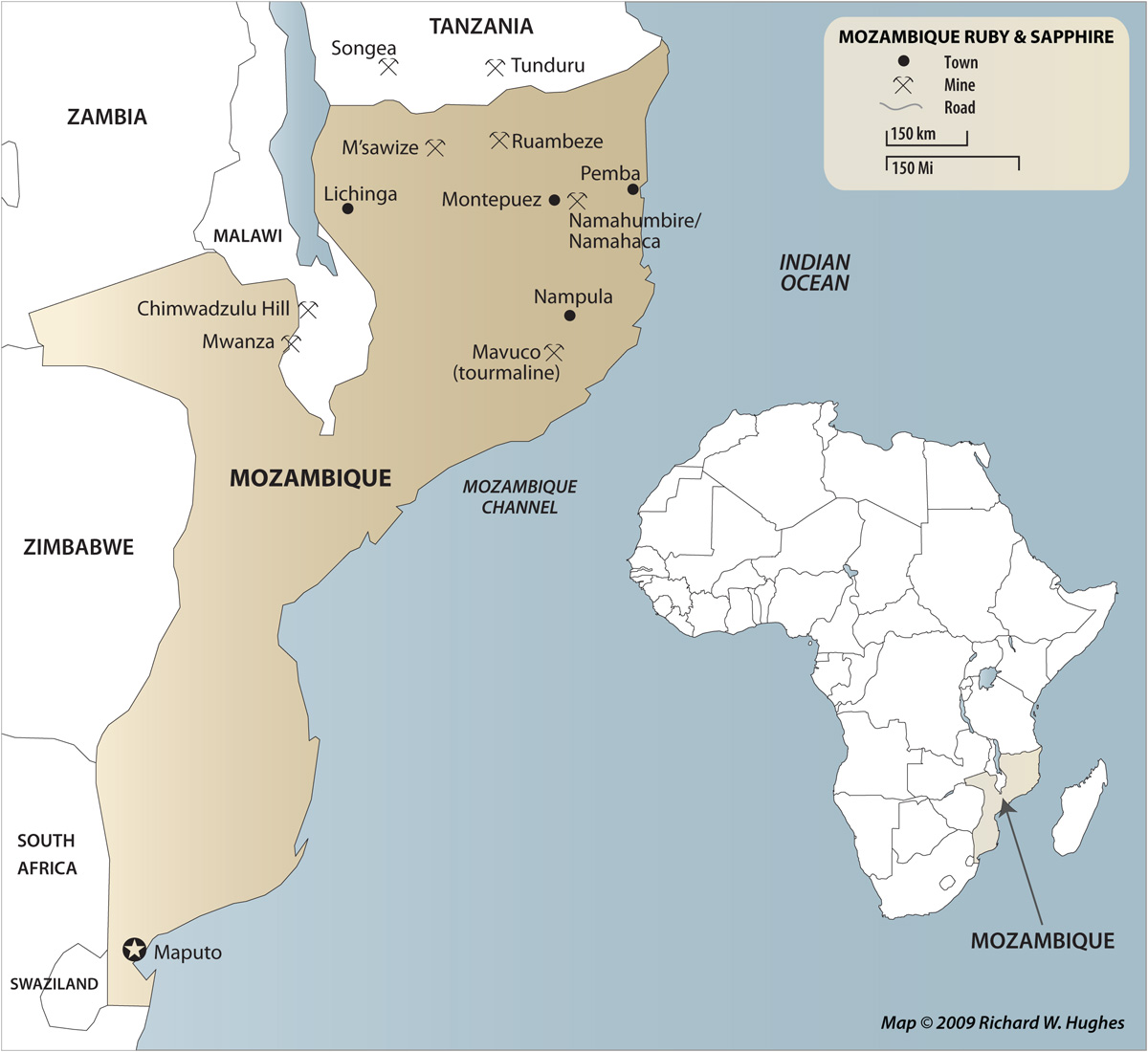

Getting

to the mine is no easy task, of course. There are flights from Dubai to

Tanzania and then onto Pemba, on Mozambique’s northern coast – where a tiny

airport and convoluted entry process highlight the area’s limited number of

tourist arrivals – and then a lengthy drive that takes us through acres of

untamed land, past abandoned colonial-era buildings and villages made of mud

huts.

The

following morning brings expansive horizons and clear, uninterrupted blue skies

– the kind that seem specific to Africa – along with a tour of the Montepuez

Ruby Mine. It’s a revelation. The mining industry has a notoriously bad

reputation, but here we are greeted with signs such as: "Stop, think,

act" and "Safety awareness saves lives", highlighting Gemfields’

aim of operating a zero-accident mine.

Every

employee we see is appropriately dressed and equipped; and there is only

minimal visible damage to the landscape, courtesy of Gemfields’ practice of

filling in old pits as mining teams move along, replanting local plant species

to bring verdant cover back to the land. We contribute to this process during

our stay, with each member of the group planting a tree as a marker of our time

spent here.

Rubies

were first discovered in Montepuez in 2009. As the story goes, a man working

the land, which was formerly a hunting concession, happened across one of the

red stones. Given the volume of rubies that we see during our trip, it seems

incredible not that they were discovered, but that they managed to remain

hidden for so long. The local owners of the land contacted Gemfields; they had

heard about the success of the company’s ethically operated emerald mine in

Zambia and wanted to replicate the model in Mozambique. Gemfields acquired a 75

per cent stake in the mine and arrived on-site in 2012.

The

team remembers trying to decide where to place their camp. They picked a spot,

started digging a hole for the latrine and promptly unearthed handfuls of

rubies. The jokingly dubbed "million-dollar toilet" stayed, and is

now flanked by the Sort House, but the camp was moved farther away.

The

sheer number of rubies here makes the mining process relatively

straightforward. This is open-pit mining – in simple terms, mountains of rich

red earth are scooped up in enormous diggers, transported to the wash plant and

processed. The rubies are then picked out from the resultant gravel by hand.

Mining

may be a controversial business, but there’s magic in it, too. There is

something indescribable about picking up a ruby and knowing that it has sat

under the Earth’s surface for hundreds of millions of years – that you are the

first person to ever touch it.

While

diamonds have dominated the market for the best part of the past century,

rubies have been coveted by certain cultures throughout the ages. "Rubies

were treasured by early cultures as they represented the redness of the blood

that flowed through their veins, and many believed that rubies held the power

of life and so were often carried into battle for protection," says Sen.

"In fact, the ruby has always been highly esteemed in Oriental countries,

being regarded as endowed with extraordinary powers. As western empires rose to

power, rubies became the favoured gemstones of European royalty and

aristocracy.

"However,

the advent of feisty diamond marketing, backed by consistent supply, in the

past three or four decades, took coloured gemstones to the background, while

diamonds took centre stage. This is now changing, with leading jewellery brands

like Chopard, Bvlgari, Cartier et al launching exclusive coloured-gemstone collections,

and with increasing incidence of ruby and emerald jewellery being sported by

celebrities around the world."

"However,

the advent of feisty diamond marketing, backed by consistent supply, in the

past three or four decades, took coloured gemstones to the background, while

diamonds took centre stage. This is now changing, with leading jewellery brands

like Chopard, Bvlgari, Cartier et al launching exclusive coloured-gemstone collections,

and with increasing incidence of ruby and emerald jewellery being sported by

celebrities around the world."

If

the tide is turning, Gemfields must be given its dues. It can now offer a

consistent supply of rubies to manufacturers and polishers, with the promise

that they have been ethically sourced and are of a guaranteed quality. Much as

it did with emeralds in Zambia, the company has also created the first official

classification system for rubies, which in addition to the standard four Cs (colour,

clarity, cut and carat) that will be familiar to any diamond buyer, includes

two other Cs: certification and character.

Beyond

logistics, Gemfields’ global marketing campaigns are contributing to creating

an aura of covetability around coloured gemstones once again. Its latest

marketing campaign, Ruby-Inspired Stories, offers a triptych of films that

explore three properties that rubies have long been associated with: passion,

prosperity and protection.

Beyond

logistics, Gemfields’ global marketing campaigns are contributing to creating

an aura of covetability around coloured gemstones once again. Its latest

marketing campaign, Ruby-Inspired Stories, offers a triptych of films that

explore three properties that rubies have long been associated with: passion,

prosperity and protection.

In

fact, unbeknownst to many, rubies are much rarer than other precious stones. At

present, the world ruby supply consists of about three million cut and polished

carats per year, compared to about five to eight million for emeralds and 50

million for diamonds, according to Ian Harebottle, chief executive of

Gemfields.

But

the company’s aim is not for coloured gemstones to overtake or replace diamonds

in the public consciousness, but to create more balance and choice in the

market. "The decade starting 2015 was actually billed as the decade of the

coloured gemstone," says Sen, when asked whether he envisages a time when

coloured gemstones will surpass diamonds in popularity. "Every time a

consumer buys a coloured gemstone, diamonds are sold alongside. Coloured

gemstones and diamonds complement each other, and that’s the way it will always

be," he says.

Gemfields

held its first ruby auction in Singapore in June 2014, and generated US$33.5

million (Dh123m). At its latest ruby auction in June, the company generated

record revenues of $44.3m (Dh162.7m), with an average realised price of $29.21

(Dh107) per carat.

Gemfields

held its first ruby auction in Singapore in June 2014, and generated US$33.5

million (Dh123m). At its latest ruby auction in June, the company generated

record revenues of $44.3m (Dh162.7m), with an average realised price of $29.21

(Dh107) per carat.

There

is much talk during our time in Mozambique about the "1 per cent".

Not the 1 per cent, that top layer of society that holds a disproportionate

share of global wealth (although that is an unfortunate parallel) – but the 1

per cent of Gemfields’ annual revenue that it donates to CSR initiatives. The

number feels small to me – as small as it can be, almost.

I

put this point to Harebottle. "Our commitment is a minimum of 1 per

cent," he says. "We are working with a luxury good in unstable

economies. We are very fortunate that through our efforts we are constantly

growing, but there are no guarantees. When I make a commitment, I have, to the

very best of my ability, barring any major catastrophes, to be sure that I am

able to keep that commitment."

The

point, of course, is that whether you are talking about 1 per cent or 100 per

cent, sustainability needs to be sustainable, or else it is entirely

counterproductive. "When people ask me about our investment in

sustainability, I say: ‘The one thing I can tell you is it doesn’t mean we are

perfect and it doesn’t mean we are doing enough.’ I’ve lived in Africa and I

know there is not a company or individual in the world that can do enough,

because the needs are so great.

"The

one thing I do know, 100 per cent, is that the areas we are in are better for

us being there. We’re doing the best we can, recognising it’s not enough and

constantly trying to do better."

And

I am reminded on numerous occasions how even one per cent can make a major

difference in a place like Mozambique. We visit some of the projects that the

company is investing in – they are very real grass-roots initiatives.

"After collaboration with the local community, a farming association was

recently formed producing beans, okra and various other vegetables. Currently,

most of the produce is being bought back by the company, where it is purchased

at market prices and used for the sustenance of its own employees," Sen

explains. "A poultry-farming cooperative has been formed at a nearby

village with a view to further empower women in the area. Going forward,

initiatives based around education (including a new skills and development

centre), health care and the provision of clean drinking water will also be put

in place. Conservation is also a focus."

Beyond

this, by implementing a professional, transparent, legal mining process,

Gemfields is taking the trade of Mozambican rubies out of the hands of illegal

syndicates, which exploit poverty-stricken members of the community, by driving

them to partake in hazardous and illegal mining work, and paying them a

fraction of the gemstones’ true worth. Illegally mined rubies are then smuggled

out of the country. Gemfields, on the other hand, will argue that it is able to

achieve the best prices for the stones, and pays taxes and royalties to the

Mozambique government (MRM is responsible for about 20 per cent of the

corporate tax in the Cabo Delgado Province), while also creating employment and

job security for members of the local community.

Beyond

this, by implementing a professional, transparent, legal mining process,

Gemfields is taking the trade of Mozambican rubies out of the hands of illegal

syndicates, which exploit poverty-stricken members of the community, by driving

them to partake in hazardous and illegal mining work, and paying them a

fraction of the gemstones’ true worth. Illegally mined rubies are then smuggled

out of the country. Gemfields, on the other hand, will argue that it is able to

achieve the best prices for the stones, and pays taxes and royalties to the

Mozambique government (MRM is responsible for about 20 per cent of the

corporate tax in the Cabo Delgado Province), while also creating employment and

job security for members of the local community.

In

a perfect world, Gemfields would not be an anomaly. Its ethical approach to

mining would be the industry norm. But we do not live in a perfect world, so

Gemfields must be lauded for its efforts. It is the only supplier of coloured

gemstones that has built a holistic business model that places importance on

people and the planet, as well as profit. It is introducing transparency in an

industry where, traditionally, there has been none.For

the first time, you can buy a ruby and know exactly where it has come from, and

that it was mined in a way that is respectful of local populations. And in this

imperfect world, that’s basically priceless.

*Read

this and more stories in Luxury magazine, out with The National on Thursday,

November 3.